♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦

As we have seen, the airship and aircraft bombings of the First World War did not damage the dock, but it fell victim to the more intense and targeted Luftwaffe bombing of the Second World War. As a strategic commercial target the docks had been targeted by German bombers and this was only one of many dock structures to be devastated. Warehouses were also hit, and one of the more notable casualties of the bombings was the Dog and Duck public house, which sat at the end of South Dock and had been there in some form since at least 1723. All that remains of it is the name of the Dog and Duck staircase, one of a whole series of watermen’s stairs that are found all along Rotherhithe’s foreshore. The lock was badly damaged and was sealed until after the war. South Dock and Greenland Dock had independent lock entrances because they had been owned by separate dock companies, but when the two docks became part of the same company a cut, named Steelyard Cut, was created to link the two, so access to South Dock was still possible via the Greenland Dock lock entrance. However, in 1944 there was a pressing need for dry docks for the construction of Mulberry Harbours, so the decision was made to cut off South Dock from Greenland Dock, sealing off Steelyard Cut to ready it for the construction of concrete sections of Mulberry units for the armed forces.

“Mulberries” were designed to meet a logistical problem to an assault on the Normandy beaches that would make a profound difference to the outcome of the war. In 1942 the British attacked the heavily fortified town of Dieppe and were turned back. But if British troops were to be landed in France, some part of the French coast would have to be breached, and it was decided that the beaches of Normandy would be the best option. But there were two problems. First, any invasion would require huge numbers of men and heavy equipment, and with no infrastructure in place to receive, unload, process and supply the invasion, and the difficulties inherent in capturing a suitable port posted a potentially massive problem. Second, troops and supplies were to be landed directly on the beaches but the coastline of Normandy featured long and shallow inclines, meaning that at low tide boats could not approach near enough to the shore to offload their cargoes. But these was the sort of problems that the armed forces were expert at solving. Churchill had had a similar idea in 1917 to cope with the capture of two islands in the Danish-Dutch seas, but the man usually credited with the idea of the Mulberry Harbours is Hugh Iorys Hughes whose brother Commodore John Hughes-Hallet presented it to the Navy. Whoever it was who came up with the idea, it was concluded that if a harbour could not be captured, then a harbour should be built, transported and then installed wherever it was needed. These were the Mulberry Harbours.

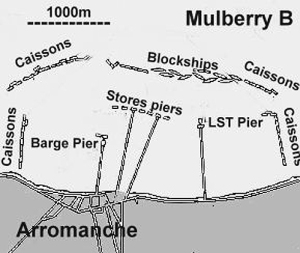

Mulberry Harbours were modular units which, when assembled, could be used to create temporary harbours along the Normandy coast. They consisted of pier-heads (known as “spud-pontoons”), piers (“whales”), inter-linked concrete pontoons “beetles”), caissons to form breakwaters (“phoenixes”) and in-shore shelters provided by ships forming a barrier (gooseberries). There is a brilliant description of how all these elements fit together on Chris Bridges’s “Mulberries and Gooseberries” page, together with some super illustrations. Floating pontoons were placed at 80ft intervals between the pier-head (where boats would dock) and the beach and carried the 80ft-long piers (whales) that formed floating roads that allowed people and cargo to be unloaded onto the shore. As the tide raised and fell, so too did the floating moorings, allowing ships to moor and offload, even at low tide. 146 caissons were required to form 9.5kms of breakwater to protect both the piers and the ships, each 60 metres long, 18 metres high and 15 metres wide. The breakwaters formed by Phoenix units, more or less parallel to the piers, and the sheltering barrier of ships called gooseberries formed protecting arms to emulate a true harbour.

After various experimental prototypes were tested, two Mulberries were assembled for deployment: Mulberry A at Omaha beach, and Mulberry B at Arromanches, each with an intended capacity of 7000 tons of vehicles and supplies a day.

Different parts of the Mulberry Harbours were manufactured in different places (much as the Airbus is today), transported to a distribution hub and were later assembled where they were needed. This was because of the sheer amount of work involved, described evocatively on the Combined Operations Command website: “The scale of the project was enormous and was in danger of over-stretching the capacity of the UK’s civil engineering industry. From late summer of 1943 onwards three hundred firms were recruited from around the country employing 40,000 to 45,000 personnel at the peak. Men from trades and backgrounds not associated with the construction industry were drafted in and given crash courses appropriate to their work. Their task was to construct 212 caissons ranging from 1672 tons to 6044 tons, 23 pier-heads and 10 miles of floating roadway.”

The component that was manufactured at South Dock was the caisson, or Phoenix, used to form the breakwaters. The contract for building twelve Phoenix B sections in Rotherhithe was given to John Mowlem, a civil engineering company, in late 1943. The Phoenix units were airtight cases made of concrete and steel that were open at the bottom. Although they look fairly boxy, they were shaped at bow and stern ends to resemble barges on the grounds that they would have to be sea-worthy both when being towed and when in position. They were designed to float and were fitted with air-cocks so that they could be lowered evenly to rest on the sea-bed. Eight were to be built at South Dock, four at Russia Dock (also on Rotherhithe) as well as another six at East India Dock on the north of the Thames. South Dock was turned into a dry dock by Mowlems, who drained the dock, sealing it with a concrete barrier at the lock and blocking the cut that connected South Dock to Greenland Dock. The base of the dock was then covered with 6ft of rubble to ready it for the construction of concrete sections of the Mulberry units. South Dock must have been a strange sight with no water in it. The above photograph from the Imperial War Museum shows what the units looked like when under construction at South Dock. It is a truly spectacular scene! The photo has been taken the eastern edge of Rotherhithe, looking over the Phoenix units towards Greenland Dock, which is still filled with water and has a ship in dock. The sheer number of cranes that serviced both docks is impressive – many of the crane tracks still exist but there’s nothing like seeing a photograph of what it was all like in action.

On the 17th March 1944 the Phoenix sections under construction at South Dock had all been completed. Steelyard Cut, which still links South Dock with Greenland Dock, was re-opened, the dock was refilled via Greenland Dock, and the Phoenix sections were floated out first through the cut, with only 9 inches of clearance and then out onto the Thames through Greenland Dock’s entrance lock, and transported downriver and out to British coastal destinations. Each was fitted for the journey with a small crew, a temporary cabin and an anti-aircraft gun, which came into use when a German bomber flew low to take a closer look and was fired upon. Many of the caissons were initially sunk to hide them from German spy planes, and were re-floated, with some difficulty, when ready for deployment in France.

For the next part of the story click here: The Dog and Duck Public House